Workplaces Are Families Too

2 July 2025

Written by Toni Hanna

What Families and Workplaces Have in Common – Exploring the invisible dynamics that shape how we relate, lead, and belong.

Modern Western society has a habit of splitting things into parts. So, it’s common in workplaces to expect people to do the same: leave your personal self at the door when coming to work. If you are a parent or partner, you’re expected to leave that at home and show up in your professional identity. If you’re a person with a disability or of a different cultural identity, you’re asked to leave it behind and assume a role in the workplace that claims to be neutral - but can still recognises those differences, sometimes in ways that feel less than welcoming.

For some people, this has become normal practice. For others, it feels unnatural and even alienating. It’s important to remember that people are human beings first; then come the identities of age, gender, culture, relationship, parenthood, and employee status.

Instead of interrupting or denying what is natural in life - that is, to assume many roles and varied identities - we need to welcome and embrace each other in all our roles and identities. If we don’t, we set people up to be in conflict with themselves and their roles. We undermine their capacity to bring their full self to their work. Denial contributes to unsafe spaces, leading to protective behaviours that block creativity and diminish engagement and productivity.

Another common trait of Western society is to value certain characteristics or behaviours over others. Separating and pulling some skills into isolation is risky - and, over time, can lead to imbalance in both people and society. For example, quick thinking and decision-making may be highly valued. But when decisions are made without consultation and context, the consequences can be far-reaching and take much longer to resolve.

Adults differentiate between roles and spaces to know which identity to step into, and when. It’s also true that most people struggle with boundaries at some point in their lives. On occasions personal lives spill into the work environment. Other times we allow work to invade our homes. In either setting, attention to the people or tasks at hand is compromised, creating tension and pressure in the group - especially in hybrid or high-stress environments where the lines blur more easily.

As much as workplaces drill into their staff that “work is work” and personal lives must remain at home, it is my observation and experience that whenever people form in groups, a mini community is created. Large or small, workplaces are a kind of family. The question is: what kind of family is it?

Is the leadership of the organisation respectful, fair, and inclusive of all its members, services, or programs - especially those that are less visible or less immediately profitable? Or does it favour some over others? Are certain individuals overworked? Do employees experience diAerences in expectations, workload, and attitudes toward them? Is this related to age, gender, cultural identity - or all of the above?

The dynamics we grow up with - in our families, communities, and cultures - don’t vanish when we walk into work. They show up in how we relate, how we lead, and how we respond to pressure.

To explore how these deeper patterns can play out in an organisation, let’s look at a familiar scenario - one where the workplace begins to resemble a family, with all the complexity and consequence that brings.

When Workplaces Mirror Families: Who Gets Fed, and Who Goes Hungry?

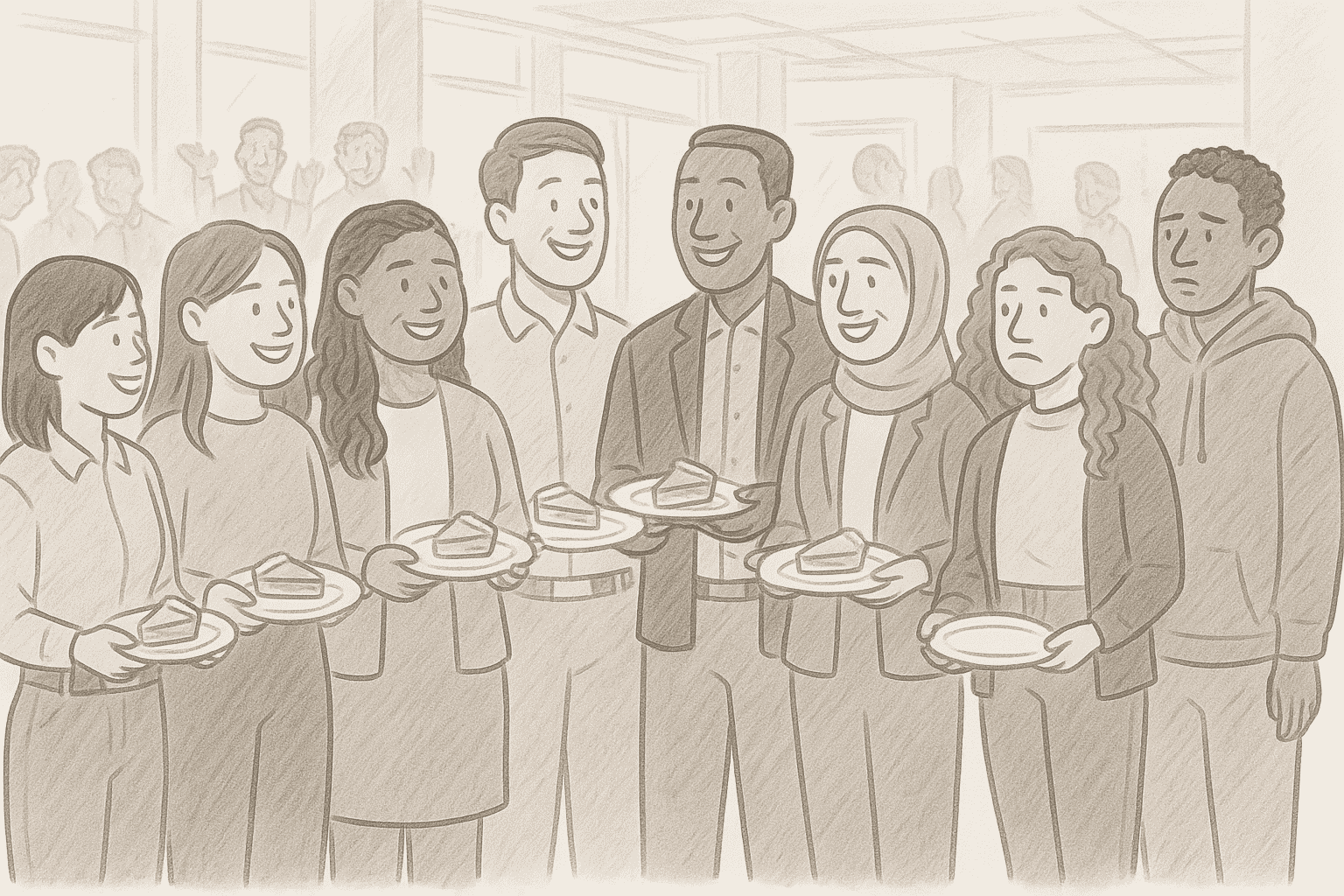

Let’s take a small organisation - around 100 employees. Like a family, the organisation has siblings: well-established, stable programs that are supported by consistent funding. Then there’s the baby of the family: a preventive-focused initiative. It’s not necessarily the newest program, but its preventive nature - addressing issues before they escalate - often places it lower on the priority list when it comes to funding. It’s smaller, less secure, and its survival depends on the overflow from the more established programs. Ironically, it’s this quieter role - the one designed to reduce harm before it begins - that can be most at risk when newer, more marketable programs are introduced.

Now imagine this organisation keeps growing - new initiatives are introduced, new directions celebrated - but the funding pie remains the same. It’s like sitting down for dinner with the same amount of food, but more mouths to feed. Someone is bound to go hungry. In this case, it’s the smallest. Her portion is quietly redirected to support the newest arrival - the shiny, exciting addition that holds more perceived value.

In organisational terms, the CEO, Deputy CEO, and Senior Managers are the primary decision makers - much like the parent figures in a family system. When resources are tight, it’s these leaders who divvy up the food. And as programs multiply without a corresponding increase in funding, hard choices are made.

The smallest - the under-resourced initiative - starts to notice her plate shrinking. For months, she's been scraping by. Eventually, she’s told she’s no longer viable. The food has run out. Or more accurately, her share is being redirected elsewhere.

It didn’t have to be this way.

If handled differently, she would have been included from the beginning - consulted when talk of growing the family first emerged. A collaborative process might not have saved the program, but it could have honoured her contribution. Instead, she’s kept in the dark, left out of the conversation entirely. She finds out too late that her program is being shut down.

This manager - a committed staff member - has spent years building a community presence, forming partnerships with external organisations, nurturing waiting lists of eager clients, and strengthening the organisation’s visibility. When the news breaks, she fights to stay afloat - not just for her job, but for the people relying on the service. She wins six more months, but spends that time closing down, wrapping up loose ends, and quietly slipping out the door. No public thanks. No recognition. Just gone.

Decades older than the newborn program that replaced her - and yet, it’s like she never existed. What followed wasn’t just the quiet closure of a program - it marked the beginning of an overall unravelling within the organisation.

When decisions are made without transparency and consulting the people they impact, the damage goes deeper than just one team or role. It’s a systemic issue that affects the trust, cohesion, and relational fabric of the whole organisation. In my experience, when these dynamics are handled poorly, it can lead to an exodus of staff - and with them goes corporate knowledge, team cohesion, and the spirit and culture of the organisation.

On the outside, it may still look like paradise. But inside, it's desertified. What emerges in its place is a kind of starved, alien-like creature - full of limbs and functions, but strangely hollow, fed by something unrecognisable. A far cry from the robust, human, relationship-centred organisation it once was.

It’s not to give employers and managers a hard time. Managing people - like raising a family - requires the highest level of relational skills. At Shemewé Collective we understand that family dynamics don’t just stay in the home - they’re alive in our teams, our leadership structures, and the way we respond to each other under stress. If we want workplaces that are truly healthy, we need to support the leadership and people within them to understand and shift those dynamics - not just at home, but wherever they arise.

Shemewé Collective offer two confidential workplace-based programs - Conscious Parenting and Relationship Rescue - designed to meet people where life actually happens: in their families, their partnerships, and their inner worlds. These confidential relationship groups don’t sit on the sidelines of professional life; they support the very dynamics that shape how people show up at work - how they communicate, navigate stress, manage power, and build trust. By investing in relational wellbeing, organisations not only care for their people - they create the conditions for healthier teams, stronger leadership, and a culture where people feel safe, seen, and supported to bring their whole selves to work.

Learn more about how Conscious Parenting and Relationship Rescue can support your team - and help bring relational wellbeing into the heart of your organisation.