The Meaning Behind She and He in Shemewé

Written by Toni Hanna

11 min read

Shemewé (pronounced Shem-a-way) is a social theory that emerged through observing, reflecting on and contemplating individuality and collective identity. It explores each aspect as an entity, and in relationship with the other, 'She,' and 'He', 'Me', and 'We'

It represents the space we each inhabit; the feminised (She), masculinised (He), the part of us that’s beyond classification (Me), and that which is in relationship with everything and everyone around us (We).

Shemewé believe in every human being's birthright to express both the feminised (she) and masculinised (he) aspects of their nature, regardless of gender, age, or cultural identity. It also accepts that human survival drives not only a need for secure attachments to significant others (We), but also an expression of one's unique authentic self (Me).

It offers an opportunity to contemplate these aspects in oneself and the social world, including how they shape our relationships and wider cultural patterns. The aspect of Shemewé explored in this article is the meaning behind She and He.

Observing the She and He

The She and He first took shape in my awareness as a teenager. With curiosity, I observed the behaviours and listened to what was said, and left unsaid, in the interactions between the adult women and men around me. Some values and attitudes toward gender I actively resisted, especially those that felt disrespectful. Others I absorbed more unconsciously. I continue to examine, reshape, and release limiting beliefs and attitudes inherited from the dominant culture. Shemewé breaks out of the commonly held gendered view, offering us a more holistic, integrated perspective.

How She and He Are Revealed in Social Systems

In my twenties, I began to see how the internal dynamics of She and He were reflected in the world around me and reinforced or suppressed by social systems. I also learned that the two hemispheres of my brain allowed me to perceive, process, and express information in very different ways. One was not superior to the other, and it became clear that integration is key to higher-level functioning.

My observations confirmed how the systems and institutions in the world I was in, were designed to deliver information in a way that failed to embrace the variety of people and needs within the community. One way of operating was accepted and normalised, rather than cultivating an openness to and respect for varied approaches to life and the delivery of services. Difference is not something to overcome but something inherent to who we are. One way should not dominate at the expense of the other.

The society I live in is lopsided. It rarely values the blending of detail with big-picture understanding. We see this in how scientific research is delivered: findings that are extracted, isolated, and presented without meaningful context. The same imbalance appears in education and health systems. Learning remains focused on content delivery over embodied and relational approaches. Health funding prioritises illness over wellness, sidelining more integrative models that are often labelled unscientific or fringe, despite medicine’s more holistic origins.

Shemewé offers a guiding framework that challenges the one-sided values and rigid constructs often perpetuated by dominant cultural systems. Shemewé Collective brings this vision into practice by creating spaces where integration is not just valued but experienced, countering the fragmentation so often reinforced by modern systems.

How She and He Are Revealed in Culture

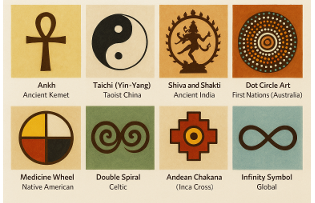

My reflections led me to explore how cultural worldviews either honour or fragment the She and He within us, influencing how we relate to ourselves, each other, and nature. In traditional societies, people use not only both hemispheres of the brain but their body, senses and relationships to learn, share and store knowledge. This way of interacting with life feels more natural to me yet is often seen by wider society as 'less than.'

Why is the written word valued above oral traditions and practices that carry the wisdom of First Peoples? Why is knowledge from traditional societies so often dismissed, when it connects us to our shared origins?

The dominant culture around me lacks integration, and is shaped by consumerism, overwork, and control rather than care, community, and accountability.

From First Peoples I’ve learned that wellbeing is an outcome of cultures that are integrated and communal, where practices like singing, storytelling, and shared meals are not ‘add-ons’ but essential ways of being. Rather than treatments for ill health, they are expressions of health itself.

As community structures have broken down in Western society, so too has our connection to each other and ourselves. Isolation becomes the new normal, and with it comes a rise in illness. In response, we construct a healthcare industry to treat the symptoms of disconnection. What we’re left with is a society fragmented into parts, disintegrated at every level.

At Shemewé Collective, we honour the deeper wisdom found in inclusive, connected cultures, offering programs that reclaim care, community, and balance as everyday practices.

How She and He Are Revealed in Relationships

These patterns also show up in our closest relationships, particularly for couples, often creating tension where there could be complementarity.

I’ve observed that rigid gender roles and the socialisation of men and women often set us up to fail as couples. My work in the family and relationship sector has repeatedly affirmed this, especially when those roles are assumed rather than consciously agreed to. To better understand how these roles influence our relationships, it helped me to look at the social and cultural forces that shape them.

Roles and socialisation are complex and layered. My reflections here are drawn from my lived experience, professional practice, and the Shemewé framework to consider how opposites, differences, and conflicting ideologies work against, for, and with one another.

Within Shemewé, the She and He represent distinct, sometimes opposing parts of ourselves, mirrored in the social structures we live within.

In many traditional societies roles were more fluid, interchangeable and shared. In recent Western history, many couples were assigned roles, one as provider, the other as homemaker. Each role had its own specific objective, held within and supported by a mostly gendered community.

In our present times, I’ve observed that the provider role can become oriented toward serving work or the wider world, where competition, status, and power can for some gradually replace care and presence to the family, ultimately becoming self-serving.

Meanwhile, responsibilities traditionally associated with the homemaker role are often distributed across grandparents, childcare centres, cleaners, and food delivery services. This is a practical necessity for many, though not accessible to all. Yet the person who identifies with this role frequently carries the bulk, if not all, of the responsibility for the unseen labour of home, family, and relationship. This includes not only practical tasks like cooking, cleaning, organising, and caring, but also the emotional and mental load of sustaining connection, often in addition to paid work.

Many people living in affluent cities are sure these stereotypes have been overcome. But my work with couples and families over several decades shows they are still strong, often hidden beneath a thin layer of gender-neutral appearances. Instead of being complementary, differences often become oppositional, creating obstacles for couples to work through, making it difficult for them to succeed.

I’ve come to question whether relationship breakdowns are not only due to the couple but also shaped by the gendered socialisation that sets them up to miss the mark and ultimately to fail.

A clear example is the persistent challenge in communication for partners. I’ve seen how difficult it can be for one party to identify, name and responsibly express their emotions. Withdrawal, silence or angry outbursts commonly result. The other party, however, is focused on maintaining connection. They neglect their own needs, perhaps expecting their partner to understand or meet them.

Naturally such a dynamic can foster resentment and misunderstanding and all too often leads to relationship breakdown. These patterns, I believe, are not just interpersonal, they’re shaped by the roles and emotional norms gendered socialisation trains us into from an early age.

Shemewé breaks out of gender stereotypes, encouraging integration of all parts in oneself, our relationships, and communities. At Shemewé Collective, we support couples and parents not just to cope in isolation. We believe the wellbeing of families has always belonged to the village, and today, that village includes the workplace. Our programs invite organisations to lead with support that allows families and relationships to thrive, not just for productivity, but for the long-term health and cohesion of the people who keep our communities going.

The Emergence of Shemewé

In 2016, the term Shemewé came to me, surfacing in my awareness. At first, I saw the She, the He, and the We, but something still felt missing. I knew the missing part would reveal itself, so I stayed open and ready to receive it. Once the final piece, the Me landed, I knew it was complete. I didn't like the sound of each pronoun being enunciated so I accented it to Shemewé (Shem-a-way) which is easier to pronounce.

In a society that breaks everything into parts, even the human body, it makes sense that Shemewé was born out of a search for reintegration and reconnection, both individually and socially.

A Framework That Continues to Evolve

Since then, Shemewé has continued to shape my thinking. I see it less as something I created, and more as a framework that emerged through observation, reflection, and dialogue. It continues to inform how I understand people, systems, and the spaces between them.

With Shemewé, I came to understand that She and He are not assigned to people but are expressions that live in each of us. At first, this was difficult to explain because She is usually associated with woman, and He with man. Over time, it became easier to show that both the feminised and masculinised are shaped by the dominant culture we belong to. There’s no single way of perceiving these expressions, though many share overlapping interpretations. Rather than define the characteristics of each, I’m more interested in encouraging acceptance of difference, not one better than the other, but each essential for our higher functioning as humans

Shemewé invites us to reclaim what has been excluded, neglected, or undervalued, and to recognise how unbalanced dynamics, often shaped by dominant norms, transfer power, responsibility, and emotional labour unequally.

At Shemewé Collective, we create spaces that welcome overlooked voices and bridge the gaps left by outdated norms, spaces where meaningful connection and shared humanity are not only possible, but prioritised.

Shemewé in the Workplace

Throughout this article, I’ve explored how the She and He live within us, and how their imbalance plays out in our relationships and dominant culture. Many of the tensions we see around burnout, communication breakdown, leadership disconnect, and emotional isolation are not just personal, they’re structural and cultural.

At Shemewé Collective, we offer culturally safe workplace programs that respond directly to these dynamics. Our We Belong EAP and Private services focus on people from diverse cultural backgrounds and the LGBTIQAP+ community. These are often the people whose voices are undervalued, silenced, or excluded within dominant workplace cultures. Our LGBTIQAP+ inclusive EAP services go beyond crisis support, restoring dignity, connection, and agency.

Our We Belong specialist services for men explore how rigid roles or attachments to masculine identity can limit capacity for empathy, accountability, and emotional presence. The inclusive strategies for men’s wellbeing we introduce broaden the scope of what strength, care, and connection can look like at work and in life.

Conscious Parenting and Relationship Rescue, our two online groups, provide muchneeded, preventive workplace support for parents and couples, two cohorts often overlooked in community wellbeing strategies.

Shemewé Collective integrate gender-responsive leadership training and programs to support emotional wellbeing in the workplace, helping leaders and teams develop emotional literacy and relational insight. These are critical skills in today’s landscape, especially when exploring how to address burnout and communication breakdown or how to create a culture of belonging at work.

Shemewé Collective is not about choosing one part over another. It’s about restoring harmony by reclaiming what’s been lost, in ourselves, in our relationships, and in the cultures we create together. If you're an organisation ready to explore a restorative approach to wellbeing, leadership, and connection, I’d love to hear from you.